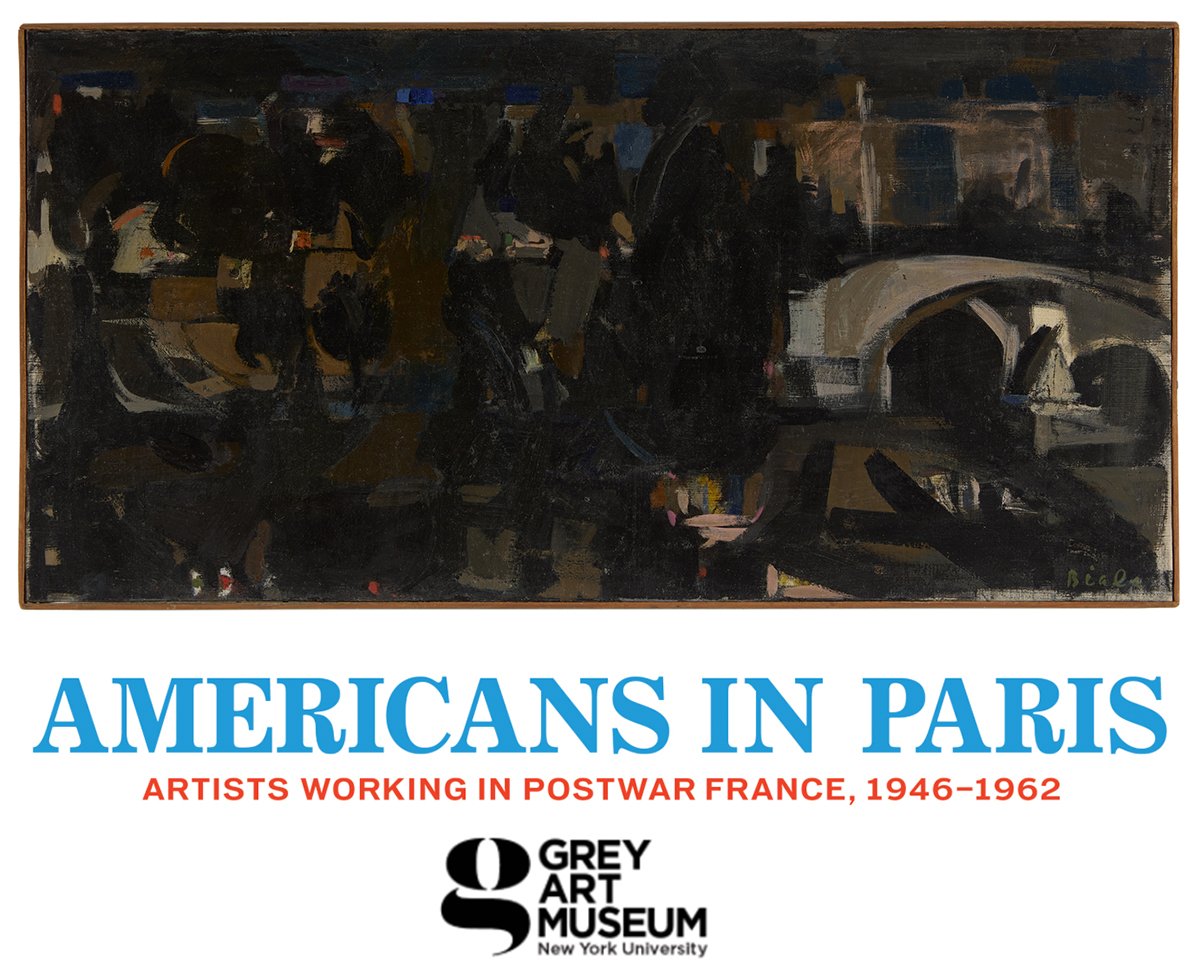

Exhibition News: Americans in Paris at The Grey Art Museum (Mar 2-Jul 20)

Janice Biala (1903-2000) La Seine: Paris la Nuit, 1954, Oil on canvas, 18 x 36 3/8 in (48.3 x 92.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

AMERICANS IN PARIS

Artist Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962

March 2-July 20, 2024

The Grey Art Museum

18 Cooper Square

NYC

Following World War II, hundreds of artists from the United States flocked to the City of Light, which for centuries had been heralded as an artistic mecca and international cultural capital. Americans in Paris explores a vibrant community of expatriates who lived in France for a year or more during the period from 1946 to 1962. Many were ex-soldiers who took advantage of a newly enacted GI Bill, which covered tuition and living expenses; others, including women, financed their own sojourns.

Showcased here are some 130 paintings, sculptures, photographs, films, textiles, and works on paper by nearly 70 artists, providing a fresh perspective on a creative ferment too often overshadowed by the contemporaneous ascendency of the New York art scene. The show focuses on a diverse core of twenty-five artists—some who are established, even canonical, figures, and others who have yet to receive the recognition their work deserves. A complementary section dubbed the “Salon” combines works by French and foreign artists that the Americans would have seen in Parisian galleries or annual salons, alongside examples by compatriots who likewise spent at least a year residing in France during this time.

While the U.S. art scene was dominated by the rise of Abstract Expressionism, Americans working in Paris experimented with a range of formal strategies and various approaches to both abstraction and figuration. And, as the esteemed writer James Baldwin—a longtime French resident—saliently observed, living in Paris afforded expats the opportunity to question what it meant to be an American artist at midcentury. For some, Paris promised a society less constrained by racism and the exclusionary power structures of the New York art world.

American artists also encountered undercurrents of nationalistic tension, as French critics sought to maintain Paris’s artistic preeminence. By 1962, the year that concludes the exhibition, many felt that the once-inspiring atmosphere had diminished. That same year, Algeria achieved independence from France after many years of demonstrations and riots, and, ultimately, war. Many Americans opted to return to the U.S., which was experiencing a burgeoning civil rights movement, and in particular to New York, where there were more opportunities to exhibit, due in part to the rise of artist-run galleries. Others chose to remain abroad. Whether they returned or remained in Paris, the Americans’ encounters with French collections, artists, critics, and gallerists significantly impacted the development of postwar American art.

Exhibition News: Biala / 40 yrs of painting at Berry Campbell (Mar 14-Apr 13)

Biala (1903-2000) "Le Louvre," 1948, oil on canvas, 36 x 28 1/4 in (91.4 x 71.8 cm) [CR753]

Biala: Paintings, 1946-1986

March 14 - April 13, 2024

Opening reception: Thursday, March 14, 6-8pm

Berry Campbell

524 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

_________

NEW YORK, NY – Berry Campbell and the Estate of Janice Biala are pleased to announce a major survey of paintings by Janice Biala (1903-2000). The survey featuring over 20 paintings dating from 1946 to 1986, marks the largest gallery exhibition of Biala's work mounted in New York City with many works on view for the first time. A fully illustrated 100-page catalogue accompanies the exhibition which includes introduction by Mary Gabriel, author of “The Ninth Street Women,” and essay by Jason Andrew, manager and curator of the Estate of Janice Biala. This historic presentation coincides with the Grey Art Museum’s seminal exhibition “Americans in Paris, 1946-1962: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962,” opening March 2 in which Biala will be featured.

"Portrait of Biala" photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

© Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

One of the most inventive artists of the 20th Century, and the painter most closely aligned with the continuation of a transatlantic Modernist dialogue between Paris and New York, Janice Biala (1903-2000), led a legendary life: a painter recognized for her distinctive style that combined the sublime assimilation of the School of Paris and the gestural virtuosity of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism.

Biala rose from humble yet tumultuous beginnings as a Jewish immigrant from Russian occupied Poland arriving in New York in 1913 settling among the tenements of the Lower East Side. She claimed the name of her birthplace for her own, going on to make personal and unique contributions to the rise of Modernism both in Paris and New York.

Having spent the decade of the 1930s as the last companion to the English novelist, Ford Madox Ford, Biala was the perfect representative of American bohemia in 1930s France and her journey as an artist evolved in tandem with the historic events of the 20th century.

Highlighting this survey is a pivotal group of paintings dating from 1947 to1952. On view for the first time in New York, these works were painted by Biala upon her triumphant return to Paris in 1947 aboard the de Grasse, one of the first passenger transatlantic ships to sail from New York to Europe after World War II. Her return was also a joyous one, “I still find in France all the things I’d hoped for,” she wrote her brother Jack Tworkov, “I’d have no use for Paradise if it wasn’t like France.” These works offer an extraordinary opportunity to see Biala’s close connection to European Modernists like Picasso and Matisse, both of whom she had frequently met.

“Though her themes of still life and interiors, landscapes and portraiture remained constant, her approach to portraying them evolved,” writes Jason Andrew in essay for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition:

“Impressionism is a term rarely used in discussing Biala’s work, but it fits with her sensitivity and narrative. Never liberal with factual description in her paintings, Biala pulls us in through a balance of subtle truths—the hard edge of a table, the soft outline of a figure, the dark shadow of a building. It’s a tender abstraction that feels lived in, and one which she honed very early on from her mentor Edwin Dickinson and heightened by the vigilant study of the narratives crafted by Ford Madox Ford.”

Biala (1903-2000) "Nature Morte à la Table," 1948, Oil on canvas, 31 1/4 x 45 in (79.4 x 114.3 cm) [CR754]

“Le Louvre,” 1948, is among this group and one of the first paintings to fully capture the architecture of Biala's adopted city. A seminal work, the painting features a view of the city from the Left Bank looking North across the Seine with views of the Louvre and the Jardins des Champs-Élysées. More specifically, Pavillon de la Trémoille appears on the upper left and the various rooftops that make up the Louvre filling the horizon. Pont de Arts stretches horizontally through the painting’s center left. Framing the composition is an iron railing in the near foreground.

Alongside this historic group of paintings, Berry Campbell will present important large-scale works including multi-paneled paintings which bridge American and European traditions—portraying a synthesis of cultures and emotions. As an example, the two paneled work “Intérieur à grand plans noirs, blancs, rose,” 1972, on view for the first time, embraces Biala’s suggestive approach to space. “Here the continuity of reading the painting from left to right is deprioritized in order to offer multiple vignettes—evocative impressions and multiple views of an interior where angles are represented by juxtaposition of color,” writes Jason Andrew.

Biala (1903-2000) "Les Fleurs," 1973, acrylic on canvas (three parts), overall: 45 x 108 in (114.3 x 276.9 cm) [CR066]

In the epic three paneled painting “Les Fleurs,” 1973, three differing perspectives vie for sovereignty as each offers an individually composed interior with bold and blocked in color—bare of human presence. Here the flourishing potted flowers bring the personality.

The exhibition also features a gallery dedicated to Biala’s works on paper and in particular, her collage work. As the artist noted, towards the end of the 1950s, her transatlantic returns from Paris to New York took their toll on her paintings. So, she turned her attention to collage. Embracing the “immediate effects,” which “you can’t possibly get in painting,” Biala embarked on an intense exploration of the medium. The subjects in Biala’s collages range from intimate interiors to the wild and thrilling portrayal of a cassowary.

For checklist and press inquires: info@berrycampbell

Biala and de Kooning

Biala, “Le Duo,” 1945, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 25 5/8 in (91.8 x 65.1 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala

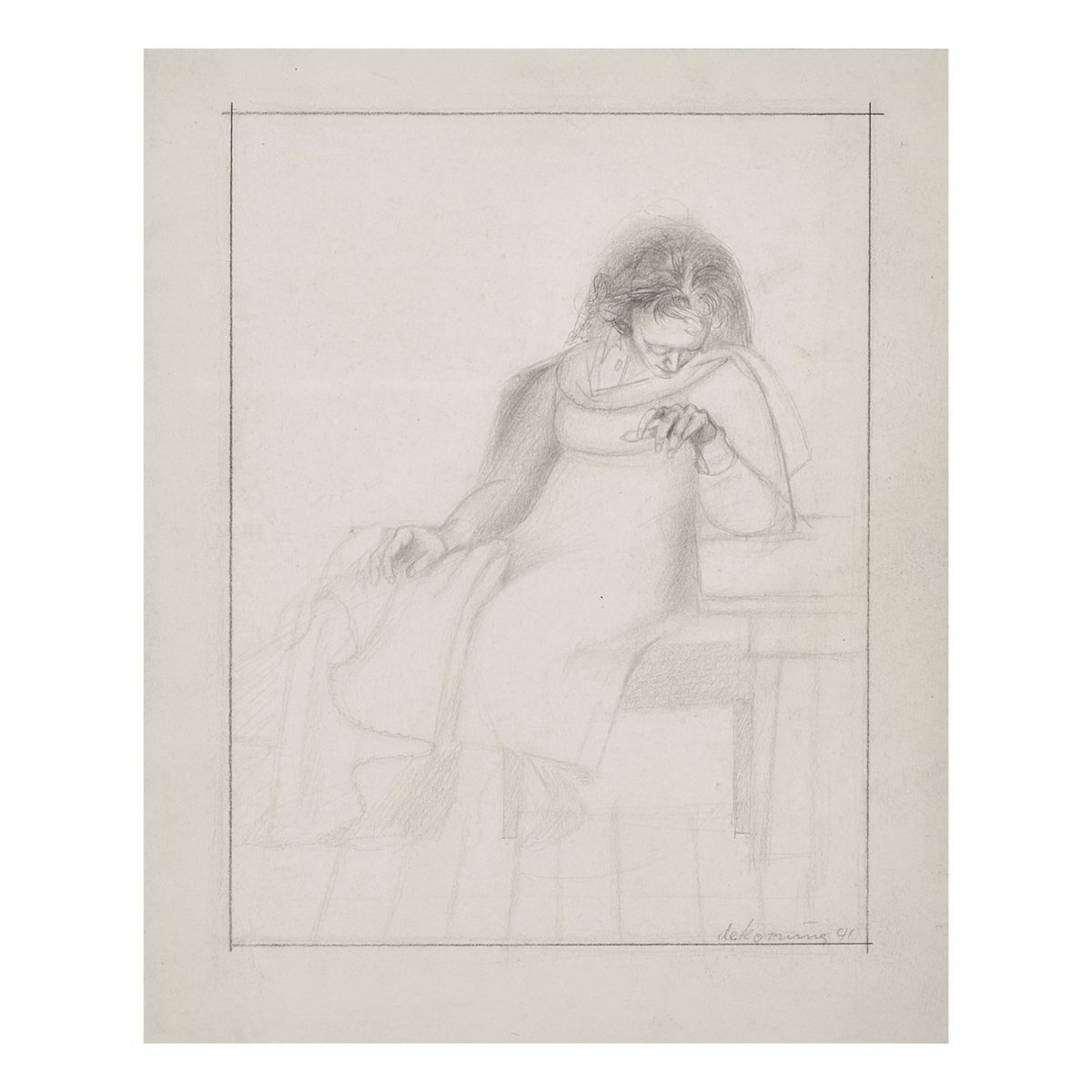

This fall, Christie’s New York will offer works by Willem de Kooning formerly from the collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. Biala and Alain were among Willem de Kooning’s earliest patrons.

Visit Christie’s to learn more about these works.

Janice Biala emigrated to the United States from Russian-occupied Poland in 1913 with her older brother, Jack Tworkov. As adolescents, the siblings decamped to Greenwich Village and became immersed in the bohemian life. Like her brother, Janice is an avid reader, with The Three Musketeers being her favorite book. She would later tell French novelist and art theorist André Malraux that it was because of Porthos that she became an artist. During a fateful trip from New York to Paris in 1930, Biala met and fell in love with the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. A formidable figure among writers, artists and the transatlantic intelligentsia, Ford introduced Biala to the many artists within his circle forging a new Modernism in France including Constantin Brancusi, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. Upon Ford’s death in 1939, Biala fled Europe under the growing Nazi threat, rescuing Ford’s personal library and manuscripts while carrying as much of her own work as she could.

Re-establishing herself in New York City, Biala met and married the Alsace-born Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. The couple became a fixture among the rising avant-garde artists living and working around Washington Square. Through her brother, Jack Tworkov, Biala met Willem de Kooning who had built out studio space in a second-floor walkup at a storefront at 85 Fourth Avenue and was renting half to Tworkov. Tworkov and de Kooning had met originally while working for the WPA during the 1930s.

“De Kooning didn’t seem to be painting much then,” Tworkov told de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, “but toward the end of the thirties, [he] began to work a great deal and I began noticing it. At that time some of us began to think that he was a great artist, and we became friendly.”

Biala and Alain in a public square in Paris, c. 1948. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archives, New York

As offered by Stevens and Swan:

So glowing was the description of de Kooning that Biala immediately took an interest in the Dutchman’s art. Soon, she met and married an artist named Alain (Daniel) Brustlein, whose cartoons regularly appeared in The New Yorker. ‘So when Alain and I were married, Alain said, “Well, if (de Kooning’s) as good as you say he is, and if I like his work, I’ll buy one of his pictures,’” said Biala […] “So sure enough we went over there to de Kooning’s loft and he saw a picture [an abstract painting of 1938] that he liked and he bought it. This was probably in 1942.” – de Kooning: An American Master (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) p.177

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) is considered among the most rare and informative early paintings still in private hands. The work was included in a historic survey of de Kooning work at the Museum of Modern Art, organized by Thomas Hess in 1968. The painting is featured in the publication accompanying the exhibition as Hess describes:

“In his abstractions the space is a flat, slippery, metaphysical surface, related to that of some Mirós of the middle thirties; there are also recollections of Arp. The forms are based on the strip (usually vertical, related to Mondrian) and circles that have been forced into pointed or bulging ovals by the irregular pressures between shapes. This lateral pushing and pulling is held flat to the surface by bright colors (often keyed to blue and pink with parallel grays and ochers); their values are so close that, in Fairfield Porter’s phrase, they make 'your eyes rock.’” (p.25)

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) was not the only work by de Kooning that Alain and Biala would acquire. Because of Alain’s notoriety as an illustrator for The New Yorker, the couple had the means and would become important early patrons of de Kooning's work. “We bought a number of pictures from de Kooning because he needed the money.” Biala told Stevens and Swan. (p.177) And according to Stevens and Swan, Biala and Alain didn’t behave as most collectors did, trying to get the best possible price. “We’re not collectors,” Biala said, “We paid him the regular price. We were the only people who did that, Bill told Alain. We bought Woman [a turquoise and pink painting of 1944] and paid $700 for it, which at the time was a pretty good price.” (p.177)

de Koonings painting “Abstract Still Life” can be seen here, upper left in her own painting which features Alain playing the cello and Eliane de Kooning playing the piano.

Beyond supporting de Kooning through the purchasing of work directly from the studio, Biala worked tirelessly to find him a gallery. She would introduce him to her own dealer, Georges Keller, who was the director of the Bignou Gallery credited for introducing modern French painting like Bonnard, Cézanne, Corot, Dufy, Matisse, Picasso, and Renoir to New York collectors. “It took me years to get Keller to come down to see his paintings,” said Biala. “Then he did, and he was very impressed. He took two paintings and three drawings.” (p.179) And yet, the best Keller would do was include de Kooning in a “quiet group exhibition of 1943,” which paled in comparison to the riotous rage made by the rise of Surrealism. When Bignou closed in 1949, he gave Biala, with de Kooning’s permission, the three drawings. It is believed that these drawings are Study for ‘Glazier’ (c.1938-39), Untitled (Massacre Scene) (1941), and Seated Woman (1941).

When de Kooning married Elaine Fried on December 8, 1943, it was Biala and Alain who hosted a “spontaneous, informal and extremely simple wedding lunch at a cafeteria.” Making the otherwise “bleak” event more celebratory. (Stevens and Swan, p. 197)

The many paintings and drawings by de Kooning that were acquired by Biala and Alain, hold historic significance; reflecting not only a sharp scene of connoisseurship, but the impeccable provenance of an intimate friendship.

Willem de Kooning, “Figure,” 1944, oil on Masonite, 19 1/2 x 16 1/8 in. Formerly from the Collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein

Biala Paints a Picture: Summers in Spoleto

Biala (1903-2000) “Open Window: Spolète,” (1965-1968), oil on canvas, 63 3/4 x 44 3/4 in (161.9 x 113.7 cm) Photo Roz Akin

During the summers of 1965-1968, Biala attended the Festival dei Due Mondi in Spoleto. Her stay inspired several paintings and works on paper. Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Janice Biala, takes a took at one painting above all which celebrates Biala’s love, friendship, and appreciation of Henri Matisse.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) “Open Window, Collioure,” 1905, oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 18 1/8 in (55.25 x 46.04 cm) Collection National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney (1998.74.7)

Biala discovered for the first time the works of Matisse when the Brooklyn Museum opened an exhibition of French painting in the spring of 1921. It was a lasting and profound experience, one after which both Biala and her older brother Jack Tworkov decided to dedicate their lives to becoming artists. Tworkov said he “never forgot the impact of Cézanne, whose ‘anxieties and difficulties’ came to mean more to him than Matisse’s liberty and sophistication.” Biala on the other hand, though drawn to Cézanne’s structured compositions, would come to assimilate Matisse’s color and sensibility.

Biala first met Matisse during the decade of the 1930s by way of introduction through her lover and companion, the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. Biala would meet Matisse again visiting him in early 1954. Upon hearing of the death of the artist, Biala wrote that she “always had Matisse in my belly.”

Widely described as an icon of early modernism, Matisse’s small but explosive work titled Open Window, Collioure (1905), is heralded as one of the most important early paintings in the style of les Fauves.

Like Matisse’s Open Window, Biala’s painting belies an optical and conceptual complexity in which conventional representation is subordinated throughout by other pictorial concerns. Both paintings offer a vantage point upon a vantage point as the view moves from the interior of a room, to the open window, to the view point of the landscape beyond. In the case of Matisse, he offers the view of Collioure and the densely packed view of boats rocking on the French Mediterranean coast. For Biala, she offers a view of Spoleto the mountainous city in Umbria, Italy, which at the time had been reinvented by the summer Festival dei Due Mondi.

Biala first traveled to Spoleto in the summer of 1965 at the invitation of her friend the “the doyenne of international culture,” Priscilla Morgan, who at the time was the associate director of the beloved festival. Morgan is credited with bringing about a renaissance to the festival extending invitations to other artists, Isamu Noguchi, Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller and musicians Philip Glass, Lukas Foss, and Charles Wadsworth among others.

Biala painted Spolète over three years likely taking sketches back to her Paris studio in the 7th arrondissement made from her summer visits. Subtly incorporating a series of variations on variations, this painting is Biala’s perfect assimilation of both the School of Paris and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism.

This historic work is now available at Berry Campbell.

Exhibition News: Biala at Whitechapel

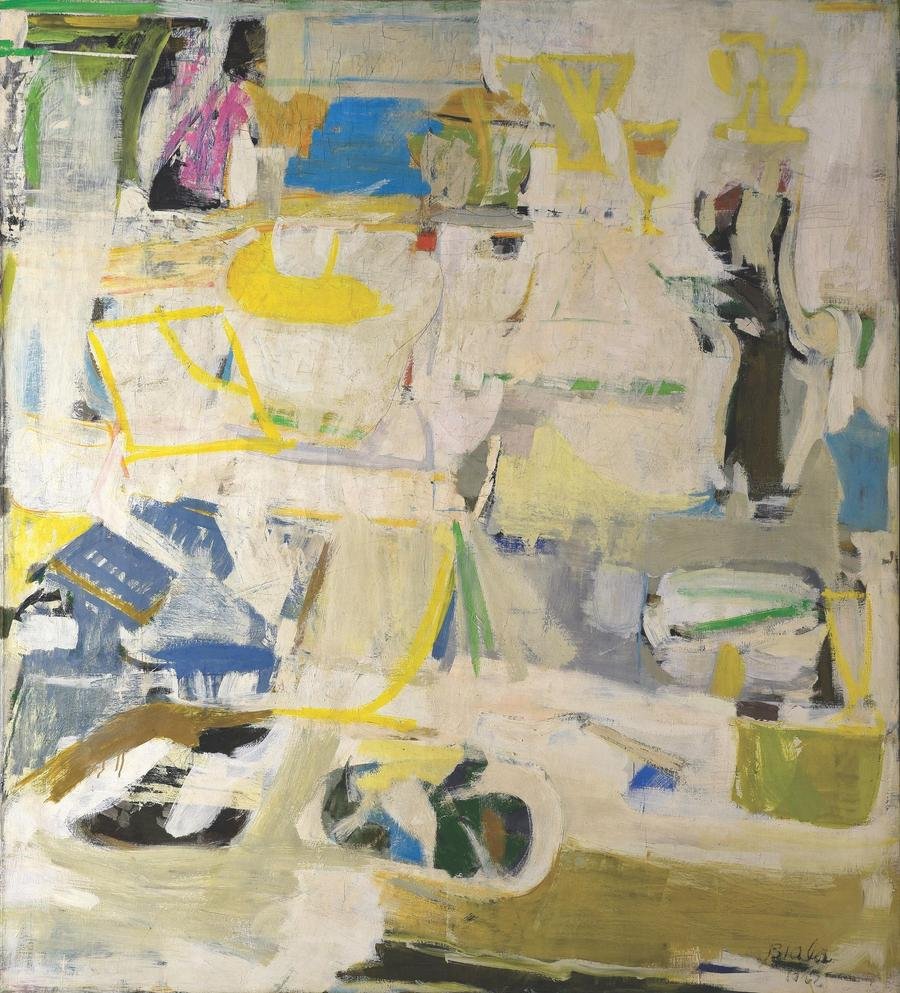

Janice Biala, Yellow Still Life, c.1955, oil on canvas, 162.6 x 129.5 cm. Courtesy The Christian Levett Collection © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70

9 February – 7 May 2023

Whitechapel Gallery

77-82 Whitechapel High St

London

★★★★ A ‘kaleidoscopically varied exhibition’ – The Telegraph

★★★★ ‘You can’t have too much of a good thing, and this show is full of good things’ – Time Out

‘Bursting with feeling…‘ – Financial Times

Whitechapel Gallery presents a major exhibition of 150 paintings from an overlooked generation of 81 international women artists.

Reaching beyond the predominantly white, male painters whose names are synonymous with the Abstract Expressionist movement, this exhibition celebrates the practices of the numerous international women artists working with gestural abstraction in the aftermath of the Second World War.

It is often said that the Abstract Expressionist movement began in the USA, but this exhibition’s geographic breadth demonstrates that artists from all over the world were exploring similar themes of materiality, freedom of expression, perception and gesture, endowing gestural abstraction with their own specific cultural contexts – from the rise of fascism in parts of South America and East Asia to the influence of Communism in Eastern Europe and China.

The exhibition features well-known artists associated with the Abstract Expressionism movement, including American artists Lee Krasner (1908-1984) and Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), alongside lesser-known figures such as Mozambican-Italian artist Bertina Lopes (1924-2012) and South Korean artist Wook-kyung Choi (1940-1985). More than half of the works have never before been on public display in the UK.

Article: "Peintresses en France: Janice Biala" via DIACRITIK

Biala working on canvas at the apartment of the critic Harold Rosenberg, with the painting “Two Young Girls,” c.1953. Courtesy Estate of Janice Biala. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Paintresses in France (15) : Janice Biala (1903-2000), Painting for Country

by Carine Chichereau

Published in DIACRITIK

December 15, 2022

The following is the complete English version translated by Noémie Jennifer Bonnet from the original with permission from the author and DIACRITIK. Click here for the original article in French.

Biala in her Paris apartment, 1947. Photo: Henri Cartier-Bresson © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

Outside of painting, Janice Biala had two great loves in her life: France, and the writer Ford Madox Ford. Born in a large garrison town in Poland, then under tsarist Russian rule, she expanded her horizons at a young age, discovering New York and the bohemian Greenwich Village, Provincetown back when it was still a village of artists and fishermen, and the buzzing Parisian scene of the interwar period, where she met Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Piet Mondrian, among others. After fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe, she championed Willem de Kooning’s work, participated in the founding of abstract expressionism in New York alongside the biggest artists of the era, and eventually settled back in France, like Joan Mitchell and Shirley Jaffe, where she became part of the so-called “School of Paris.” Her life ended as the twentieth century came to a close.

Biala is a bridge between Europe and America, between modernism and abstraction. Biala signifies eight decades of artistic practice covering nearly the entire 20th century, yet whose inimitable style is instantly recognizable. Biala is a paintress with a steel will, who never ceased to fight and adapt to difficult circumstances. She went so far as to change her name and nationality, while never renouncing her identity, and in the end she found her place among the greats of her time, despite being born female and Jewish in the empire of the tsars.

Biala’s story begins at the close of the nineteenth century, and ends at the threshold of the twenty-first. Schenehaia Tworkovska was born September 11, 1903 in Biala Podlaska, a largely Jewish garrison town that held great importance to the Russian empire that ruled Poland at the time. Her father, a tailor named Hyman Tworkovsky, already had many children. Following the death of his first wife, he marries Esther, who gives birth to Yakov in 1900 and Schenehaia in 1903. In 1910, likely hoping for a better future for himself and his family, Hyman Tworkovsky decides to emigrate to the United States, at first taking only with him the children from his first marriage, who are all approaching adulthood. A cousin named Bernstein serves as a “sponsor” for the cause of “family reunification.” However, for this to work, a shared last name is a requirement: thus Hyman Tworkovsky becomes Herman Bernstein.

“Biala’s life is a novel, a theater of all the upheavals of the 20th century.”

“White Still Life,” 1951, oil on canvas, (66 x 91.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

What kind of childhood did Schenehaia lead, alone with her brother and mother in a military town, in the early years of the twentieth century before everything exploded? Did children draw back then? Did the absence of their father and siblings cause them to suffer? How did they cope with the uprooting of their lives, three years later, and the long one-way voyage to a new land? During this time, their father has been able to establish his business as a tailor in Manhattan, and he brings them over as soon as he can. At the time, European migrants arriving at Ellis Island by the millions, many of them hailing from Eastern Europe, many of them Jews who feared persecution. What are the odds of a ten year-old girl born into poverty becoming an internationally recognized artist in a foreign land that speaks a foreign language?

After a transatlantic voyage that, for a child, must have been as terrifying as it was exciting, she arrives in New York on September 26, 1913. I can easily envision a Biala painting with an unadorned view of the port, in pinkish hues, a hazy statue of Liberty in the horizon, the symbol of possibility. Is their future rosy? Not at first.

“L’atelier du Marché Saint-Honoré,” 1982, oil on canvas, (96.5 x 144.8 cm), private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

As soon as they set foot in America, Schenehaia and Yakov Tworkovsky are reborn as Janice and Jack Bernstein. The entire family piles inside the father’s tailor shop, located in tenement housing for the poor. At the time, the Lower East Side was teeming with destitute immigrants who would stop at nothing to reinvent themselves and build a new life. Janice and Jack are no different: both siblings possess that extraordinary adaptive ability to transform every obstacle into an opportunity, every challenge into possibility. A fruitful rivalry quickly develops between them, and they will remain close throughout their lives, primarily thanks to a regular correspondence. We know very little of their youth, but one can imagine them in school working side by side, learning English,taking on the occasional odd job. One can imagine the cultural and linguistic shock they must have felt with nothing familiar in sight, save for a few family members.

They must have adapted quickly to their new environment, because, in their late adolescence, seeking something more than their parents could offer, Jack brings his sister along to settle in Greenwich Village, the hub for artists and bohemia since 1850. Together, they decide to take back their given family name, minus its last syllable. They become known as Janice and Jack Tworkov. He attends Columbia University, aspiring to become a writer or journalist, but everything changes one spring day in 1921. Epiphany strikes.

On view at the Brooklyn Museum at that time was the first exhibition in the United States of the paintings of Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. For Janice and Jack, it’s a shock to the system. He is enchanted by Cézanne; she is enthralled by Matisse. She is 18 years old, and sweeps her brother toward painting. From then on, she knows what she wants and enrolls (with her brother) in the National Academy of Design, grabbing every odd job possible in order to finance her studies—working in sales at Macy’s, or as an employee of the telegraph company Western Union. Having discovered the paintings of Edwin Dickinson through a winter exhibition at the National Academy of Design, in 1923, Janice persuades Jack to go spend the whole summer in Provincetown, and they hitchhike the whole way there.

Janice’s meeting with Dickinson would prove foundational to her development. One need only look at his paintings to understand the lineage: a denuded version of reality; pared-down landscapes; flat, subtle tones circumscribing space; and colors that hold together the composition. Dickinson teaches his apprentice to focus on essentials, to go beyond what she sees in order to extract an abstract vision in two dimensions. He insists that color harmony is more important than the representation of subject. For him, the starting point of a painting is a dab of color, or rather two: “Two dabs of color on the same plane, which is of course necessary because you can’t have just one color. They all exist in relation to a common harmony.”

Biala is a colorist. And her usage of color—assimilated very quickly at Edwin Dickinson’s side, as far from realism as it is from sentimentalism—makes her a modernist like her mentor. In 1937, during a lecture to the Colony Club at Oberlin College, she goes even further: “The very first spot of paint that you put on your canvas sets the note for everything that must follow. Just as in writing a novel, and no doubt in music and the other arts, every word you write must lead up to your climax, and no word or phrase must be there just because you happen to like it, so each spot of paint in your picture must lead up to some definite movement and must connect with every other spot of paint in the picture. Because red is not red by itself; its full quality of redness only becomes apparent when it has green beside it or the full quality of green is brought out only when it has purple beside it and so forth. Then against the color you play your forms, lines and texture.”

Jack is taken with life in Provincetown, but Janice decides to return to the bohemian society of the Greenwich Village. It is Provincetown, however, that hosts her first group exhibition in 1927. By the end of the 1920s, she is gaining traction and exhibiting in galleries like G.R.D. Studio, which birthed the careers of many young artists of the time. In parallel, she remains active in the artist colonies of Woodstock and Provincetown, becoming friends with Blanche Lazzell, Dorothy Loeb, and William Zorach, and keeping close ties with Edwin Dickinson. The stock crisis of 1929 leaves her in dire straits: galleries are no longer selling and unemployment hits a record high. In the midst of all this, she marries the painter Lee Gatch on a whim.

She writes then, “If I ever get a hundred dollars, I’m going to Europe and stay there.” In April 1930, her friend, the poet Eileen Lake, invites her to Paris. The stars align as two wealthy art patrons offer to pay for her trip. Around the same time, she decides to follow the advice of the painter William Zorach, and changes her name again. She writes to Jack, “I decided to change my name in order not to be confused with you [...] My name is now Biala. It’s not a bad idea if I want to continue to paint.” Amid all these changes, she comes to understand that painting is the only thing she knows how to do. Sadly, very few works from this period have survived.

“Snow in the Courtyard,” 1976, oil on canvas (119.4 x 120.7 cm) Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The Violin,” 1924, oil on canvas, (55.9 x 53.3 cm) Collection of the City of Provincetown. Donation of Jay and Pat Saffrom. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The very first spot of paint that you put on your canvas sets the note for everything that must follow.”–Biala, 1937

“Yellow Still Life,” 1955, oil on canvas (162.6 x 132.1 cm). Private collection, France. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In hindsight, the year 1930 truly appears to be a decisive moment in Biala’s career. At 27 years of age, she is a strong, opinionated free thinker who decides to take her existence in her own hands, carrying her past experiences and artistic training in tow. Shortly after obtaining American citizenship, she leaves the United States and liberates herself from the destiny chosen for her by her father. Instead she invests fully in her painting; she carves some space away from a talented brother who might easily overshadow her; and she severs a conjugal knot tied too soon, clearing a path towards what will be her greatest love story. Simply put, she reinvents herself.

At this time, Janice Biala’s favorite book is The Three Musketeers. Later on, she will say it was because of the Porthos character that she became an artist. Surely it is this literary sensibility that leads her, shortly after her arrival in Paris, to accompany her friend Eileen Lake to Ford Madox Ford’s weekly Thursday salon. She is dying to meet Ezra Pound, who is scheduled to be there that day but never shows up. Biala, disappointed, ends up sitting next to the host, whose accomplishments she ignores. Yet the 56 year-old writer happens to be one of the most successful English authors of the time. He is an absolute workaholic who has published over sixty books, founded two literary magazines, and also works as a critic and editor—the first to publish James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. He also happens to be quite the ladies’ man, having racked up a history of consecutive relationships with one eminent woman after another, many of them writers and artists, including none other than Jean Rhys. The “long passionate dialogue” (Biala’s words) that they began on May 1, 1930 would continue until June 1939, upon Ford’s death.

All of Ford Madox Ford’s friends can plainly see that day that he is completely smitten with the young paintress, who exhibits great maturity despite her youth. After all other guests leave, Ford invites Biala and Eileen Lake to go out to eat, and they go dancing until dawn. Janice Biala and Ford Madox Ford meet a number of times in the following days, becoming inseparable after only a month. In letters to her brother, Biala does not mention Ford until their engagement four months later. At his side, she is directly immersed in the Parisian literary and artistic scene. Having lived in France since 1922, Ford knows absolutely everyone: members of the literary scene like Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound and James Joyce, as well as avant-garde artists like Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi, Juan Gris and Pablo Picasso, whom Ford regards as the greatest among them. Paris is still the center of the art world then, and artists of all nationalities train there. For a young painter from across the Atlantic, it’s a dream come true.

Ford Madox Ford knows about art, and his experience allows him to build up his partner’s confidence. In 1931, in a letter to her brother, she writes, “For the first time in my life I’m convinced that I am really an artist.” Like Edwin Dickinson, Ford encourages her to foster her own aesthetic vision, while experimenting freely and seeking the poetic essence of things, rather than remaining loyal to their appearance. Indeed, when one thinks about Janice Biala’s paintings, what comes to mind are those subtle colors with great attention to nuance: a simplified version of the world, as though she wanted us to see images stripped of all that is superficial, retaining only the essence of things. Whether a landscape, an interior scene or a still life, her canvases consistently conjure a sense of fluidity that holds realism at a distance, though one can still recognize the objects that are presented. It is the singular vision of a painter transcending reality. Never forget this quote from Biala, which captures her artistic quest so well: “I’ve always had Matisse in my belly.”

One might easily assume that the relationship between the young, petite paintress and the tall, corpulent writer, thirty years her senior, would have been unbalanced, and yet the opposite is true. For nearly ten years, they share everything: he brings his experience, introduces her to the greatest artists and writers in Europe, even organizes her first solo show in New York in 1935 at the Georgette Passedoit gallery. She brings her relentless energy and breathes in him new inspiration, helps him organize his work, handles his contracts (a weakness of his), even illustrates several of his books. Both are free spirits, focused on their artistic endeavors, uninterested in societal conventions. Money and social status hold no importance; only art counts (including the art of good living—never deprive yourself of good food and drink). So describes their bohemian life in Paris, Toulon, and later the United States. Ford writes; Biala paints.

In their early years together, Janice Biala and Ford Madox Ford travel to Germany and Italy. Together they witness the rise of fascism, which shakes them to their core. For Biala, the persecution of Jewish communities echoes the experiences of her father. As soon as Hitler assumes power, she convinces Ford to write articles in the British press denouncing the situation faced by Jews in Germany. She writes in a letter that it represents a return to the Middle Ages. She remains keenly aware of current events and a sharp critic, decrying the absence of true political efforts to stop Hitler. She is also not shy about reprimanding Ezra Pound for his fascist sympathies. In 1933, she writes to her brother: “All of the world’s cruelty and misery stem from a lack of imagination. Thus I believe that liberating our imaginations can save us, and only art can do this.” It is hard to imagine a more fervent defense of the value of art.

Simultaneously, her career gains traction. In 1932, she is invited to participate in an important artistic project titled “1940,” held at the Porte de Versailles exhibition center. It is her first large group exhibition, with four of her works on view. Organized by the Association Artistique, the exhibition aims to push the envelope, and includes many abstract works. Female artists hailing from different European countries are invited to participate; other than Biala, Alexander Calder is the only American artist in the show. The exhibition includes Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Francis Picabia and Piet Mondrian. In 1938 and 1939, Biala is offered a solo exhibition at Gallery Zak in Paris. Towards the end of the 1930s, she travels frequently to the U.S. with Ford Madox Ford, as his fame leads to numerous writer’s residencies and professorships. This allows Biala to maintain ties to the American art world and exhibit in several U.S. cities. Sadly, upon their return to France, in June 1939, on a vessel headed for Normandy, Ford falls terribly ill and has to be hospitalized in Deauville. He dies on June 26, leaving Biala devastated. Quickly, she commits to keeping her beloved’s literary legacy alive. Many of their works were stored in the house they occupied for years near Toulon. From this point on, she sets two goals for herself: to paint, and to preserve Ford Madox Ford’s legacy. War breaks out, and the world falls apart at a moment she is herself in pieces. In a letter, she calls it a “war against the spirit.” Despite a lack of funds, she manages to return to Toulon, where she packs up six or seven canvases along with Ford’s manuscripts and his precious correspondence. She barely manages to board the last ship to the United States, and by mid-November 1939, she finds herself back in New York, where a new life awaits her.

“Portrait of the writer (Ford Madox Ford)” 1938, oil on canvas (81.3 x 66 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The Flower Pots” 1985, oil on canvas (132.1 x 96.5 cm). Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

« Porte de l’Umilta (Pont de l’humilité) », 1985, oil on canvas (diptych), (195.6 x 261.6 cm), Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Back in the United States, she reunites with Edwin Dickinson in Provincetown, and most importantly with her brother Jack Tworkov, who has since become a well-known painter with many connections. Thanks to him, she finds a place in the New York scene, slated to replace Paris as the center of the art world. In 1941, she begins exhibiting with the Bignou Gallery. By this point, however, Janice Biala is a broken woman who has lost her greatest love, and been forced out of the country she had chosen to build a life. In spite of all this, she continues to paint non-stop; it is likely the only thing keeping her alive. She goes for frequent walks with a sketchbook at her side. One day, while drawing on the beach at Coney Island, accompanied only by a bottle of whiskey, a large, fairly attractive man taps her on the shoulder. His name is Daniel Brustlein, soon-to-be her second biggest relationship.

Daniel Brustlein was born in Mulhouse in 1904. He arrived in the United States at the age of twenty after attending the Beaux-arts school in Geneva. At the time of their meeting, he is a well-known illustrator for the New Yorker, signing his illustrations as “Alain.” The two had in fact already met at a party in New York a few years earlier. This chance encounter at Coney Island—another scene that would make a good Biala painting—marks the beginning of a story that would last 55 years. They marry on July 11, 1942. Alain is at the peak of his career; his drawings have just garnered him several prestigious prizes. And Janice Biala, by then a well-known painter who never really stopped exhibiting in New York, inspires her new spouse to delve more deeply into his own painting.

Her brother, Jack Tworkov, is responsible for her introduction to Willem de Kooning. Two months later Brustlein takes her for a studio visit on her birthday, and gifts her one of the artist’s paintings. They forge a friendship. Brustlein and Biala begin collecting de Kooning’s paintings, take care of him when he gets sick, even organize a reception for his marriage to the painter Elaine Fried the following year, as he lacks the funds to do so himself. Eventually, Janice Biala manages to convince her gallerist to exhibit her friend’s paintings. She is now an influential artist, one of the few women who saw enough success to find themselves included, in 1946, in a group show at the Bignou Gallery with Giorgio De Chirico, Raoul Dufy, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault and Chaïm Soutine.

“All of the world’s cruelty and misery stem from a lack of imagination. Thus I believe that liberating our imaginations can save us, and only art can do this.” –Biala, 1933

“Green Tree,” 1958, oil on canvas (162.6 x 132.1 cm), Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

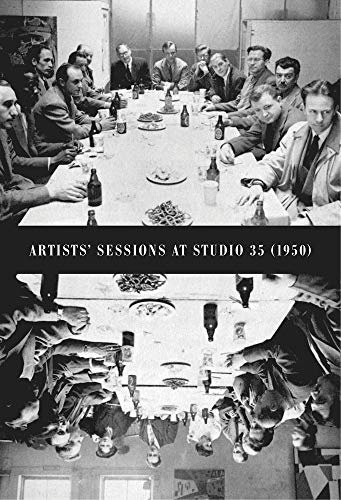

It is around this time that a disparate group of artists begins to form in New York, united by one common goal: to sever their ties with movements past—cubism, surrealism, futurism—and create something new. It is a veritable creative whirlwind—a response, certainly to the dark years of the war. In 1948, Biala participates in three days of discussion aimed at structuring this new movement, with the likes of Louise Bourgeois, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Barnett Newman. Motherwell pitches three possible designations to his colleagues: Abstract Expressionism, Abstract Symbolism, and Abstract Objectionism.An entire galaxy of artists begins to orbit around what would finally be dubbed “abstract expressionism,” even though many of them could neither be classified as abstract or expressionist. Two years later, on April 21st and 23rd, 1950, Janice Biala is again one of the few women, along with Louise Bourgeois and Hedda Sterne, to participate in a private meeting now known as “Artists Session at Studio 35,” essentially the birthplace of the abstract movement in New York. (One should not forget that this abstract movement was dominated by men both in the U.S. and in France, with only a few women admitted entry, but always kept in the background.)

From 1950 to 1965, Janice Biala traverses a period in her work focused on abstraction. She pushes to its limit a process that was already reductive, distilling reality to bare essentials. Nonetheless, most of her canvases maintain a connection to representation, albeit a tenuous one, very much unlike the Action Painters of the time, for whom gesture and the act of painting are as important as the resulting work. In contrast, Biala’s starting point is always reality, even though it is stripped, through the lens of her imagination, of all the concrete markers that anchor it to actual reality, leaving instead a kind of final essence.

“The Beach,” 1958, oil on canvas (124.5 x 83.8 cm) Art Enterprises, Ltd, Chicago, IL. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

During this period, she keeps one foot in New York and the other in Paris. In 1947, Biala and Brustlein board a ship destined for France. They befriend Henri Cartier-Bresson aboard the vessel, and the photographer agrees to rent them his studio in Paris. In a letter to Jack Tworkov dated December 3, 1947, she writes, “I’ve found all I ever wanted in France. Heaven doesn’t interest me if it doesn’t look like France.” Forty years later, in 1989, while reminiscing about her experiences in Paris and New York in an interview with the New York Times journalist Michael Brenson, she is quoted as saying, “I fell in love with France. In some ways, it reminded me of the place I was born in. And when I came to France I felt as if I had come home. I smelled the same smells of bread baking and dogs going around in a very busy way, you know, as if they knew what they were about. It really was extraordinarily human. I hadn't known when I was in New York that the skyscrapers were weighing on me, and I felt as if they had suddenly fallen off. [...] There's a certain sweetness in life here which I think is very much lacking in a city like New York.” Seven years have passed since her escape from Nazi invasion, seven years during which she has rebuilt her life, remarried, and advanced her career. She regularly exhibits in New York, and the same is true of Paris as of 1948, at the Jeanne Bucher gallery and the Salon des Surindépendants.

Upon her arrival in France, she carries the halo of the New York school’s latest current: she is in the perfect position to spread the gospel to French artists, and everyone wants a piece. She reunites with old friends, including Matisse and Picasso. Conversely, all of the American artists visiting Paris pay her a visit as soon as they arrive, hoping for an introduction to the Parisian scene: it is a nonstop parade that she laments in her letters. Numerous are the artists looking to settle in Paris back then, such as Ellsworth Kelly, and notably, Shirley Jaffe in 1949, then Joan Mitchell in 1955.

Did Paris offer an environment more favorable to female painters in the second half of the 20th century? To hear Joan Mitchell in a 1989 interview for that same article in The New York Times, one would certainly think so: “To me, New York is very male [...] Paris is female [...] In France, they've always said my work is violent gestural painting. In New York, they've said it's decoration. On both sides, they say it's female.” All three—Biala, Jaffe and Mitchell—are driven by color, and Mitchell adds, “There are no colorists in New York.”

“Her whole life, Biala had to fight to exist—as a woman, as a Jew, as an immigrant, and as a painter who wanted her talent to be recognized.”

“Two Young Girls (Hermine and Helen)”, 1953, oil on canvas (152.4 x 119.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Invalides II,” circa 1967, oil on canvas (101.6 x 101.6 cm), private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The 1950s are a period of both deepening development and dispersion for Biala. I say dispersion because, although they want to live in France, Biala and Brustlein cannot risk losing their American citizenship. During this somber period marked by McCarthyism and paranoia, they are legally required to return to the U.S. every two years, and remain there for a period of time in order to retain their citizenship. Every two years, they must move from one continent to the other. The painter Hermine Ford, daughter of Jack Tworkov, then a teenager, describes this period of her family history thus: “My entire childhood was characterized by their comings and goings. [...] It was wonderful when they were here. But my sister Helen and I were very scared of [Biala] when we were little. She was a tough cookie. [...] Once we got older, we loved her, she was the last survivor of the four, and Helen and I were completely devoted to her. She didn’t have kids, so she kind of appropriated her nieces, and she was such a hypocrite with us; she yelled at us because we sat with our legs too far apart, and would tell us ‘Young girls in Paris don’t sit like that.’ Meanwhile I’ve rarely ever seen her in a dress; she was a real tomboy. She was tough as nails. You had to be if you wanted to be an artist at the time. She presented herself as the woman who chain-smoked, cursed, and sat down however she liked.” Nonetheless, Biala was a very elegant woman, who had her shirts tailored in silk fabrics brought back from India, who left behind a trail of the perfume l’Heure Bleue by Guerlain, and who, according to many testimonials, remained attractive even in her old age.

“Cuisine rose,” 1969, oil on canvas (88.9 x 115.6 cm) private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In 1960, Janice Biala and Daniel Brustlein buy a house at 8, rue du Général Bertrand in the 7th arrondissement, finally settling for good in Paris. Their home is a former stable facing the interior courtyard of a building. They move in, build out each of their studios, and quickly the location itself becomes an endless pool of inspiration for Biala. She paints everything under every angle imaginable: the cat, the kitchen, the courtyard…The city of Paris itself is also a continuous source of material. She frequently paints the outskirts of the Seine, the Louvre, Notre-Dame, as well as more anonymous Parisian façades. In her studio, she crushes natural pigments with a bit of linseed oil, then dilutes them with turpentine and lays them out on a glass palette. She begins by deconstructing reality in her head, outlining shapes and volumes in order to recreate them on the canvas. In order to combat blank canvas syndrome, she quickly adds a few dabs of paint on the empty surface. The first stages of her compositions feature very few filled-in areas; she tries things out, erases when necessary with a palette knife, a razor blade, or sandpaper. She does not work from precise, finalized preparatory sketches, but continues to sketch while working on her painting, trying out ideas in her sketchbook until she is satisfied and can translate them onto canvas. If she encounters a problem midway, she goes back to drawing until she finds a solution.

In 1962, the Beaux-Arts Museum of Rennes becomes the first French museum to offer her an exhibition. In 1965, the Biala-Brustlein couple’s first shared exhibition is presented by the Beaux-Arts Museum of Paris. A long series of such exhibitions follows. The paintings of Daniel Brustlein (known as a painter’s painter) show an evident link with Biala’s work. One can easily picture how the two worked alongside each other, and they even collaborate on several projects outside of painting, among them children’s books. During this period, they live a bohemian life reminiscent of the pre-war years: friends show up, and they go out and party. Biala becomes friends with Shirley Jaffe, Joan Mitchell, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and Alberto Giacometti.

Janice Biala continues to paint and exhibit indefatigably until the end of her days. She participates most frequently in group exhibitions in the fifties and sixties, both in France and the United States, as well as Canada, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Israel and Spain. She shows frequently alongside Joan Mitchell, Vera Pagava and Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. In 1981, the critic Hilton Kramer writes in The New York Times: “Whether she draws her subjects from Venice or Provincetown or the interior of her studio in Paris, Biala is a painter of remarkable powers. The structure of her pictures often looks quite simple, but it usually turns out to be ''simple'' in the way that paintings by Marquet and certain schools of Japanese painting can be called simple. Which is to say, not simple at all. The difficulty and complexity have been refined into lean, direct gestures and a lyrical, concentrated economy of form. Especially in her landscape and seascape paintings, Biala has a wonderful sense of place and a flawless eye for the way place is defined by light.” The critic signs off by saying it is Biala’s best exhibition to date.

Throughout her career, she has had back-to-back solo exhibitions in galleries, sometimes even in museums, at least one per year. In 1990, at a remarkably vivacious ninety years of age, she changes galleries, and continues to exhibit almost yearly at the Kouros Gallery. Following the death of Daniel Brustlein on July 14, 1996, her productivity decreases considerably, and her last exhibition takes place in 1999 in New York. She dies at home in Paris on September 24, 2000.

“Pink Venice,” 1983, oil on canvas (132.1 x 195.6 cm) Current location unknown. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Le Chat aux bords verts (Ebony),” 1990, oil on canvas (81.3 x 81.3 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Her whole life, Janice Biala had to fight to exist—as a woman, as a Jew, as an immigrant, and as a painter who wanted her talent to be recognized. At the very beginning of her career, after having changed names several times already, she chose one for herself, that of her birthplace: Biala. Art is her country, and she says it best: “I'm Jewish. I was born in a country where it was better not to be Jewish. Wherever you go, you're in a sense a foreigner. I've always had the feeling that I belong where my easel is.” And yet it is difficult not to see in this choice an homage to her roots. Polish, American, French…Biala was all of these things at once.

It is difficult to imagine today all of the obstacles that this young, courageous, ambitious woman had to overcome. The question of her name is not insignificant: female artists tended to change names, often reluctantly, upon marriage for example. For a long time, women have not had control over their identity, which was handed down to them by a man through lineage or marriage. Janice Biala had understood this when she first chose to break with family tradition, then break away from a brother with the same last name, whose proximity risked overshadowing her success. She never took any of her husband’s names. During the 1940 exhibition in Paris, in 1932, a New York Times critic referred to her as “Janice Ford Biala.” She expressed her outrage in a letter to her brother: “The damn fool had to give me the wrong name (I do not sign my work as Janice Ford Biala), but what hope is there when someone thinks one paints like a slow dance of joy or some such twaddle?”

In 1953, she wrote a letter to ArtNews following their publication of an article about her work: “No one has ever written an article about me in your paper without mentioning one of my dear husbands, and now, everyone knows my secret. I also have a brother!” Here she is protesting the relentless treatment of women as creatures who could not possibly exist without a man, who are destined to exist in the shadows of their fathers, husbands and brothers, as is the case at the time for Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning or, in France, Anna-Eva Bergman. This phenomenon is often not instigated by the men in these women’s lives, but perpetuated by critics, gallerists, and an entire art world firmly anchored in a patriarchy that cannot conceive that an artist might exist autonomously, without owing her talents to a man.

“Open Window,” circa 1964, oil on canvas, (116.8 x 88.3 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Today Janice Biala is a paintress whose name is not mentioned often, despite the amplitude of her talent and œuvre. It is possible that her division across two continents has not served her legacy well, as it is difficult to exercise considerable influence without a permanent anchor in a single place. Further, during her abstract period, as she is approaching the culmination of her artistic practice, her work falls well outside of contemporary trends, namely conceptual art. In this avant-garde milieu, painting is out of style, and figurative painting even more so—even Biala’s pared-down version.

Janice Biala is therefore an artist who deserves to be rediscovered and studied, not only for her work, but also for the influential role she held in the establishment of abstract expressionism in New York, as well as her presence at the heart of the School of Paris. Biala’s life is a novel, a theater of all the upheavals of the 20th century. The ultimate destiny of this Jewish tailor’s daughter, born in tsarist Russia, is so incredible that it is hard to believe that no one has optioned the rights for a book or a movie. Janice Biala is not only a great artist; she is an important figure of the 20th century whose struggles, willfulness, and resilience can serve as an example for women today.

I want to thank Jason Andrew, who manages the estate as well as the beautiful site dedicated to Janice Biala, and where one can find absolutely everything about her, including a chronology of her life, photos of her and her work, articles, online conferences, etc. I highly recommend paying the site a visit, if only to see more works by this great artist: janicebiala.org

END

Virtual Event (Sept 14): The Shape of Freedom, Biala and Sterne: a virtual walk-thru and talk

The Shape of Freedom: a virtual walk-through with curator Daniel Zamani and conversation regarding the life and work of Janice Biala and Hedda Sterne hosted by Artist Estate Studio, LLC.

SPEAKERS:

Daniel Zamani, Curator, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany

Jason Andrew, Curator/Manager of the Estate of Janice Biala

Ekaterina Klim, Director of the ASOM collection

The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945 is currently on view at the Museum Barberini through September 25. The exhibition examines the creative interplay between Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel in transatlantic exchange and dialogue, from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War. The exhibition includes more than ninety works by around fifty artists, amongst them Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, K. O. Götz, Lee Krasner, Georges Mathieu, Joan Mitchell, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Judit Reigl, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still. The over thirty international lenders include the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate in London, the Museo nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum Frieder Burda in Baden-Baden, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. The exhibition is organized by the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, the Albertina Modern, Vienna, and the Munchmuseet, Oslo, curated by Daniel Zamani. With generous support from the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève.

Review (via de Tagesspiegel): Malen im Hier und Jetzt

Installation featuring Untitled (Three Glasses) 1962 by Janice Biala in Die Form der Freiheit: Internationale Abstraktion nach 1945 (The Form of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945). Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany, June 4-September 25, 2022. Image: Courtesy Museum Barberini

Painting in the here and now

by Fernhard Schulz

The prelude is a painting in light tones by Janice Biala. Born in 1903 in Poland, which was then part of Russia, she emigrated to the USA with her family in 1913. In 1952 she painted the picture that is now displayed so prominently in the Museum Barberini in Potsdam.

Her name is not among those mentioned in connection with post-war American art. Just as little as that of Hedda Sterne, whose dark-colored painting "NY #7" was created in 1955 and hung nearby. Only the small-format works by Jackson Pollock on the left (“The Teacup”, 1946) and Arshile Gorky on the right (“Pastorale”, 1945), who died early, provide support for the memory.

Rediscovered Artists

The start is program. With the exhibition entitled “The Form of Freedom”, curator Daniel Zamani wants to present “International Abstraction after 1945”, from Europe and North America, and wants to tread well-trodden paths and leave them at the same time. Committing by presenting works by all the artists famous as abstract artists, such as Mark Rothko , Willem de Kooning or Barnett Newman, but leaving at the same time by adding those overlooked to the list of 52 participating artists. Most of them are female artists, of whom only a few, like Lee Krasner or Helen Frankenthaler, have achieved the same visibility in the art world.

Exhibition News (via Artful Daily): The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction After 1945

The exhibition focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in western Europe.

Janice Biala, Untitled (Still Life with Three Glasses), 1962. Oil and collage on canvas, 162,6 x 145,4 cm. Collection Richard and Karen Duffy, Chicago. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 Image: McCormick Gallery, Chicago

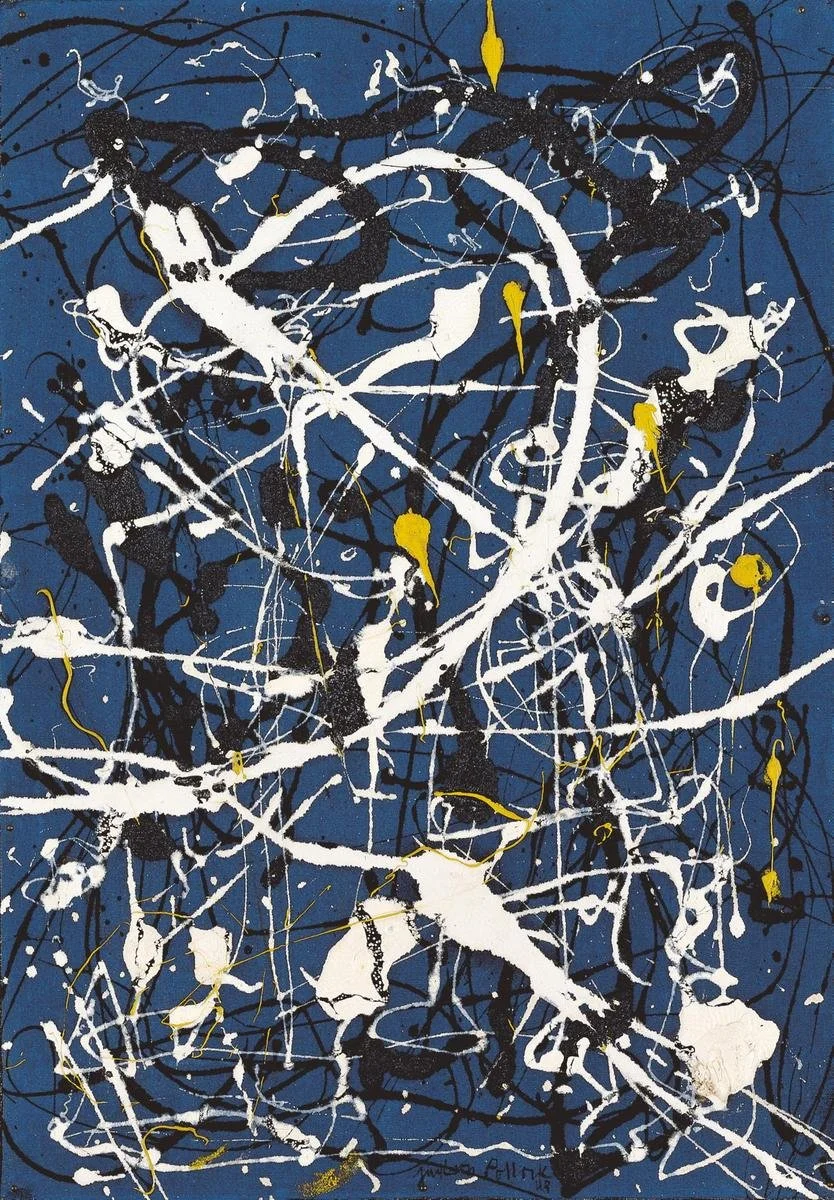

Jackson Pollock, Composition No. 16, 1948. Oil on canvas 56,5 × 39,5 cm. Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

The role of the artist, of course, has always been that of image-maker. Different times require different images. ... To my mind certain so-called abstraction is not abstraction at all. On the contrary, it is the realism of our time. - Adolph Gottlieb, 1947

The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945 is a major new traveling exhibition debuting at the Museum Barberini, in Potsdam, Germany, on June 4, 2022.

The exhibition focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in western Europe. The Shape of Freedom is the first exhibition to explore this transatlantic dialogue in art from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War.

The show comprises around 100 works by over 50 artists including Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, K. O. Götz, Georges Mathieu, Lee Krasner, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Judit Reigl, and Clyfford Still. Works on loan come from over 30 international museums and private collections including the Kunstpalast Düsseldorf, the Tate Modern in London, the Museo nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

After its opening run in Potsdam, a version of the exhibition will travel to the Albertina modern in Vienna (opening October 15, 2022) and then the Munchmuseet in Oslo.

Ortrud Westheider, Director of the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, said, “The paintings in the exhibition bear witness to the tremendous longing for artistic freedom that emerged on both sides of the Atlantic after 1945. The Hasso Plattner Collection, with important works by Norman Bluhm, Joan Mitchell, and Sam Francis, served as our point of departure. The concept developed by our curator Daniel Zamani was so convincing that the Albertina modern in Vienna and the Munchmuseet in Oslo agreed to host the exhibition as well. I am delighted to see this European cooperation.”

World War II was a turning point in the development of modern painting. The presence of exiled European avant-garde artists in America transformed New York into a center of modernism that rivaled Paris and set new artistic standards. In the mid-1940s, a young generation of artists in both the United States and Europe turned their back on the dominant stylistic directions of the interwar years. Instead of figurative painting or geometric abstraction they embraced a gestural, expressive handling of form, color, and material—a radically experimental approach that transcended traditional conceptions of painting. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann, and Joan Mitchell discovered an intersubjective form of expression in action painting, while the color field painting of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, and Clyfford Still presented viewers with an overwhelming visual experience.

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Biala and the Notre Dame paintings

Biala (1903-2000), Notre Dame II [CR 040], 1985, Oil on canvas, 51 x 77 in (132.1 x 195.6 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

As an icon of Gothic architecture, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame has inspired artists for centuries. Many artists, among them Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, would return again and again to the same vantage point throughout their careers to paint its towering magnificence.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Île de la Cité—View of Notre-Dame de Paris (February 26, 1945), 1945, Oil on canvas, 31.5 x 47.2 in (80 x 120 cm), Collection of the Museum Ludwig, Köln © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Used with permission.

Biala (1903-200), Le Louvre [CR 753], 1948, Oil on canvas, 36 x 28 1/4 in (91.4 x 71.8 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York.

Biala and her husband Daniel Brustlein boarding French Line’s SS de Grasse for Europe, 1947. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archive, New York.

Picasso, in particular, painted Notre Dame—bending the buildings, the bridges and the river into the Cubist style that he pioneered. This work, Île de la Cité-vue de Notre-Dame de Paris, painted in 1945 after the Second World War, captures Notre Dame in a softer and looser style with muted pastel colors, possibly reflecting a lighter mood of the recently liberated city.

Two years later, in the fall of 1947, Biala would return to Paris aboard French Line’s SS de Grasse—one of the first passenger boats to sail to Europe after the war. Having spent a decade alongside the English Novelist Ford Madox Ford, her return was a joyous one, “I still find in France all the things I’d hoped for. I’d have no use for Paradise if it wasn’t like France.”(1)

Using initially the studio of a new friend, the photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, and much preferring the more “human” aspects of European life, Biala began painting the City of Light from various views and perspectives. “I hadn’t known when I was in New York, that the skyscrapers were weighing on me,” she said in a 1989 interview that featured herself, Shirley Jaffe, and Joan Mitchell. In Paris, she “felt as if they had suddenly fallen off.” For Biala, Paris was “extremely beautiful and paintable.”(2)

Le Louvre, 1948, is one of the first paintings to capture the architecture of her adopted city. This masterwork features a view of the city from the Left Bank looking North across the Seine with views of the the Louvre and the Jardins des Champs-Élysées. More specifically, Pavillon de la Trémoille appears on the upper left and the various rooftops that make up the Louvre filling the horizon. Pont de Arts stretches horizontally through the painting’s center left. Framing the composition is an iron railing in the near foreground.

It didn’t take long for the Parisians to take notice of her return. In the summer of 1949, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, held her second solo exhibition in Paris—the first being in 1938 at Galerie Zak. ARTnews championed the work for its depiction of “reflected, part-dream worlds,” and, “her great sensitiveness to color, especially in the handling of yellow,” and her, “interest in peaceful things such as house-fronts, windows, life above street-noises.”(3) Later the same summer Biala became the only American among eighteen candidates selected to participate in the Prix de la Critique, receiving a special honorable mention.

White Façade [CR058], 1948, Oil on canvas, 39 x 32 in (99.1 x 81.3 cm) and Pink Façade [CR 057], 1949, Oil on canvas, 39 x 32 in (99.1 x 81.3 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

White Façade [CR 058], 1948 and Pink Façade [CR 057], 1949, are examples of the “house-fronts” mentioned in the review and were likely inspired by the apartment building Biala was renting at 52 rue de Bourgogne or a combination of façades the artist remembered from walking the city.

Certainly included in her show at Jeanne Bucher, was Biala’s Chevet de Notre Dame et e Ile St. Louis, 1949. While Picasso and Matisse and other artists preferred the more popular perspective from the West looking East towards Île de la Cité, Biala preferred to capture the cathedral from the East looking West from the Île Saint Louis.

Chevet de Notre Dame et e Île St. Louis [CR 062], 1949, Oil on canvas, 35 x 45 1/2 in (88.9 x 116.8 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York.

Chevet de Notre Dame et e Île St. Louis, is the earliest known painting by Biala of Norte Dame. Its perspective is unique, composed as if on a boat on the Seine or from the Post de la Tourney. The painting looks West towards the cathedral capturing the point where the Seine breaks around the Île de la Cité with Pont de l’Archevêché and the cathedral to the left and the Île Saint Louis to the right. Although a smaller study for this painting exists, it is unlikely that Biala painted this work (or any others) on site en plein air. It is more likely that she painted the work from a sketch or even from memory. It’s a gloomy painting developed around a palette of warm earthy hues of ochre and sage.

It is interesting to note that that summer, Biala met again Matisse spending “2 1/2 hours in his house in the company of a Life photographer who was taking pictures of him.”(4) The next day, she met Picasso again, shaking his hand.

“Paris la nuit [CR 069],” 1957, Oil on canvas, 31 x 58 1/2 in (81.3 x 148.6 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

Study for “Paris la nuit [CR 413],” c.1957, Graphite on paper, 17 x 22 in (45.7 x 55.9 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

Paris at night became the subject of two paintings dating from 1954. Similar in composition, one larger than the other, both prominently feature a bridge over the Seine. Among the gesturally painted even impressionistic midnight scene are edges of rooftops and flares of architectural details. A close study of Paris la nuit, 1957, reveals that the bridge featured is Pont du carrousel which was also a favorite of her mentor and friend Edwin Dickinson.

Biala, Notre-Dame I [CR134], 1985, Oil on canvas, 47 x 51 in (119.4 x 132.1 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

Three decades separate the next series of paintings featuring Notre-Dame. In her studio records, Biala noted four large paintings in a series she completed in 1985, two of which remain with the Estate. In the series, Pont de L’Archevêché appears prominently with the river Seine in the foreground and the towers of the cathedral. In all, the composition and palette remains quite minimal, with the bridge creating an arching horizon. Soft creamy whites and subtle hues of blue make up a consistent palette.

Biala on the left bank of the Seine, Port de Montebello, Paris, June 1979. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archives, New York

“I fell in love with France,” Biala said, “In some ways, it reminded me of the place I was born in. And when I came to France I felt as if I had come home. I smelled the same smells of bread baking and dogs going around in a very busy way, you know, as if they knew what they were about. It really was extraordinarily human.”

A photograph of Biala, taken in the summer of 1979, captures the artist at Port de Montebello at river’s edge, possibly one of the artist’s favorite and most inspiring points in Paris.

_____

1. Letter to Jack Tworkov from 65 Blvd de Clichy, Paris, December 3, 1947.

2. Brenson, Michael. “Three Artists Who Were Warmed by the City of Light.” The New York Times, Sunday, June 25, 1989, 31, 32.

3. Cunard, Nancy. "Janice Biala at Galerie Jeanne Bucher." Art News (July 17, 1949).

4. Letter to Wally Tworkov. July 31, 1949.

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Biala's first major group show in Paris — 90 years ago

Exhibition catalogue: 1940, Parc des Expositions, Porte de Versailles, Paris, January 15–February 1, 1932. Biala’s entry in highlighted text.

90 yrs ago this week: In the first weeks of 1932, Biala was invited to participate in a group exhibition titled “1940” at Parc des Expositions at the Porte de Versailles. This was Biala’s first major group exhibition in Europe and her inclusion signaled her acceptance into the Parisian avant-garde.

Alexander Calder, who had made Paris his home since 1926, was the only other American included. The tone of the exhibition, like so many presented by the Association Artistique, was provoking—wagering on the momentum of hard-core abstraction. In fact, the exhibition included many of the newly founded Abstraction-Création artists, including Piet Mondrian, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and George Vantongerloo. The exhibition also included a major retrospective exhibition of Théo van Doesburgh, who had died the year prior.

The exhibition reverberated across the pond and was all but panned by a critic for The New York Times. The headline read, 1940: Looks Singularly Out of Date:

If the Association Artistique intends that “1940” should represent a future date and that the present work presents a prophecy, they are unaware of the present trend. Many of the exhibitors have contributed compositions of squares and angles and triangles in bright colors that are no doubt the result of speculation and study in the realm of color and form. The present tendency is away from cubes, however. The present seems to be less self-conscious about the human figure and the familiar landscape and less afraid of both. Considering the times and immediate tendencies in art, Biala held true to the themes that would define her career those being the traditional subjects as still-life, portraiture and landscape. In fact the titles of the four paintings: “Le Focher” (The Rock), “Nature Morte” (Still Life), “Tete Verte” (Green Head), “Couleur de Rose” (Color of Pink).

The reviewer singled out Calder and Biala in her review. About Calder, she reported:

Alexander Calder’s metal bar and small wooden balls, a contraption looking as if it might have something to do with television, is called “January 3,” but this writer is too ignorant to appreciate the historical significance of the date.

About Biala she wrote:

Janice Ford Biala is of G. R. D. fame. The things and figures in her painting gravely turn about as if in some slow and harmonious dance of joy. Not a hilarious joy nor a country dance. Something much richer and more contemplative than hilarity.

Receiving news of her mention in the review in the form of a letter from her brother, Jack Tworkov, in true Biala fashion, she penned an aggressive response to the review back to Jack,

The damn poof had to give me the wrong name (I do not sign myself Janice Ford Biala) and what hope is there when someone thinks one paints like a slow dance of joy or some such twoddle.

At the time Biala was splitting her time between two addresses: 32, rue de Vaugirard, Paris and 5 chemin du Petit-Bois, Toulon. In both locales, she was with the English Novelist Ford Madox Ford, who she met on May Day 1930. In her letter to Jack, Biala relayed the challenges she was facing in Paris:

There are few people who think my painting is very good […] but they aren’t people of any importance. Several of them paint themselves and are most uninteresting. I’m frightfully handicapped here for being a woman and a young one at that.

While very little work dating from the time of this exhibition has survived, we know that Biala aligned herself with the modernism being generated by the likes of Picasso and Matisse, after all, it was around this time that Ezra Pound would declare her “rather modern.”

— Jason Andrew for the Estate of Janice Biala, January 2022

________

Download Exhibition Catalogue: Parc des Expositions, Porte de Versailles, Paris, 1940, January 15–February 1, 1932

Download Exhibition Review: Harris, Ruth Green. "'Les Americains' in Paris: Three Large Shows of Expatriate Painters—'1940' Looks Singularly Out of Date." The New York Times, Sunday, February 28, 1932.